Advocating for Delinquents

December 01, 2016

Ethical Educator

Scenario:

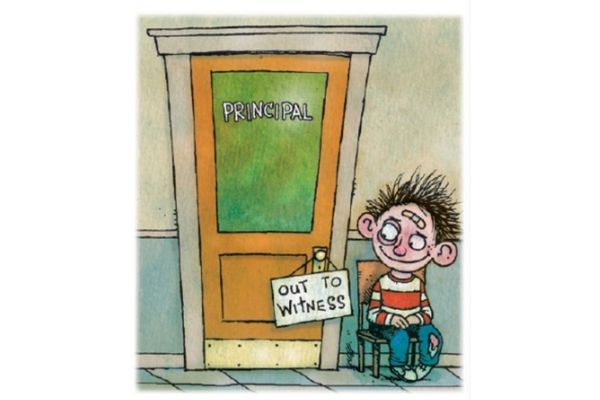

A 20-year educator now working as a middle school principal has served as a character witness and written letters on behalf of students who have been arrested, sometimes on charges of violent offenses. Because court proceedings take place during the day, the principal must ask others to cover his duties. Some colleagues take issue with this advocacy.

Is it ethical to support students charged with violence?

Shelley Berman:

The students have been charged, not convicted. An educator’s responsibility is to act in the best interest of all students, including those who have come before the court and their peers.

When asked to speak to the qualities of students whom he knows, whether in writing or as a character witness, it is both ethical and appropriate that the principal do so. To justify the time taken from his professional and personal life, he must believe these students have positive attributes worthy of the court’s consideration. As long as his input is accurate and honest as regards the students’ positive qualities and the emotional and behavioral challenges they have faced, he is contributing insights that the court can use to assess appropriate consequences for any violations of the law.

His colleagues perceive him to be advocating on behalf of individuals who have committed crimes against other community members. They may think his actions undermine the community’s confidence in the school district. They also may view his support of these students as beyond the scope of his work. In addition, his absence is a burden to them and to the district, which has to provide coverage in his absence.

The principal’s relationship with his colleagues is important. Although he may believe wholeheartedly in his support for these students, he needs to hear and appreciate colleagues’ concerns, just as they need to understand and appreciate the motivation for his stand. The superintendent should support the principal’s right to serve as a character witness, but also should facilitate a dialogue that helps the principal and his colleagues hear each other’s perspective and develop a deeper understanding of issues on both sides. Disagreement may persist about whether he should support these students to such an extent, but all parties will be better able to fairly explain the principal’s stance on the issue.

Sarah Jerome:

The middle school principal is supporting students who have demonstrated poor decision making skills. These students clearly need to be guided by caring educators to make better choices in their lives. The principal is going the extra mile to reach out to these students in their time of need. It is ethical to support students charged with violence based on the knowledge that education and guidance from caring adults can change lives and help students become better citizens in society.

A despicable action is not necessarily a path for life. When the principal demonstrates his own belief in the student, it opens a door of opportunity for the errant student to believe he/she can be better. Everyone needs to have someone who believes in them.

This principal is an advocate in school, in community and in court for students learning to be the best they can be. Letters and appearances in court are important and surely colleagues can find a way to rotate coverage if the principal is scheduled for a court appearance during the school day. Perhaps, the rotation could include teachers who are studying to become administrators. Expanding the circle may lessen the burden on other administrator colleagues and letter writing will not require a school absence.

Maggie Lopez:

The principal is a 20-year veteran who believes that the students for whom he is providing advocacy deserve to have their story told. These are middle school students who are young and may not fully comprehend the serious consequences of their actions. There may be extenuating circumstances (e.g. bullying) that drove the student to their poor choice. By speaking on behalf of these students, the principal is not dismissing the bad choices the student may have made, but rather providing information from the school perspective that may provide further context for the court. Who better than the school to provide information on the student’s school life and their patterns of behavior?

It would be helpful for the principal to have a frank discussion with his staff and clarify his decision to support a student who may have committed a violent act? How does he make that determination? What is the staff’s role in this process? Why is he the one required to go to court? Is it a principal obligation? He needs to work with his staff so they may better understand and support advocacy for these students. It also may provide the principal a chance to clarify with staff why he believes it is important to have a commitment to all kids, even in the case of a student being charged with committing a violent act.

The principal should provide as much lead time as possible when he is going to need to be in court. Hopefully he is not in court on a frequent basis, but rather on just some occasions. He needs to develop a plan that is the least disruptive for his school, while also trying to fulfill his school duties when he goes to court. Planning ahead and having several staff members who can take turns stepping in, would alleviate just a few people having to always be the ones to cover for him.

Mario Ventura:

Is it ethical to support students charged with violence? You may not like this answer, but maybe. We know that once students enter our judicial system, they begin the “school-to-prison pipeline,” making it ever so difficult to pursue a life of continued learning with opportunities to engage in society in a positive way. Often these students have some type of disability that affects learning or behavior, a history of being economically disadvantaged and may be victims themselves of abuse or neglect. Zero-Tolerance policies also play a role leading to greater numbers of students being criminalized for their behavior.

Fighting or aggravated assault in schools could at times be handled as a disciplinary infraction. Understanding students make mistakes in judgement and these mistakes and outcomes are unique in their own way, it may be better to ask if the educator has a process to determine when advocacy is appropriate. As educators, we are charged with the responsibility of ensuring the learning, well-being, and safety of all students.

However, one cannot create a situation in which advocacy for a student places other students at risk of being a victim of violence. Therefore, advocating for students should go beyond acting as a character witness. True advocacy would include working

to ensure students are provided with support such as additional educational and behavioral health services.

The Ethical Educator panel consists of

- Shelley Berman, superintendent, Andover, Mass.;

- Sarah Jerome, a retired superintendent in Arlington Heights, Ill., and an AASA past president;

- Maggie Lopez, a retired superintendent in Pueblo, Colo.; and

- Mario Ventura, superintendent, Isaac School District, Phoenix, Ariz.

Each month, School Administrator draws on actual circumstances to raise an ethical decision-making dilemma in K-12 education. Our distinguished panelists provide their own resolutions to each dilemma.

Do you have a suggestion for a dilemma to be considered?

Send it to: magazine@aasa.org.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement