BIPOC and White Leaders Learning From Each Other

August 01, 2023

Leading equity and race work districtwide is hard and messy and differs from most other change initiatives

Imagine you are participating in a series of workshops with 24 superintendents and district administrators. Half are Black, Indigenous or people of color, or BIPOC, and the others are white. You have come together to talk honestly about race and racism, to learn with and from each other to become more effective leaders of equity.

The topic this day is challenging. You are addressing the way leaders across racial differences experience what Christine Saxman and Robin DiAngelo, in their work on antiracist culture, call the unwritten rules for how BIPOC are expected to give feedback to white people on racial matters. You review their list of 21 (White) Rules of Engagement, which describe things like the tone white people want BIPOC to use when delivering feedback (e.g., trust that I’m not racist; keep me safe).

Each school system leader is asked to mark on a shared document any “rules” seen or experienced personally. The tallies highlight stark differences by race, with BIPOC participants seeing or experiencing twice as many (105 to 53) rules as their white counterparts.

You discuss the disparities, then anonymously post the impact these have on you. BIPOC comments include:

I feel invalidated, unseen in my full humanity, trivialized.

Every action taken must revolve around what white people are comfortable with.

Being me is usually misinterpreted as angry, when what I am is passionate. I have to hide my feelings so that my white counterparts remain comfortable.

White school administrators write:

I overthink my interactions because I do not want to make a mistake or offend anyone. By worrying about a potential conflict, I am not as present or direct.

I consider myself a learner, but sometimes feel that if I don’t speak up then maybe no one will. It should not be the burden of my BIPOC colleagues to be the speakers on issues of race, but I also end up qualifying anything that I do say.

As a group, you discuss the insights gleaned from this exercise about leading for equity in education.

A Cross-Racial Approach

This workshop was one of eight in a series the Massachusetts Association of School Superintendents asked us to facilitate in 2021-22. The statewide association considered setting up a white superintendent network like one described in the March 2021 School Administrator “Confronting Racism Together,” but superintendent Darcy Fernandes, a co-planner of MASS’s Race Equity Diversity Inclusion initiative, objected strongly, saying “We are not going to do that kind of professional development for white superintendents and not include superintendents of color.” In partnership with Fernandes and co-planner Karla Baehr, we developed this series.

We met monthly for two hours on Zoom, mostly as a full group of 24, with about half of the sessions deliberately split into racial affinity groupings where white and BIPOC leaders could separately process their own perceptions, work on their racial identity development and learn without anyone feeling blamed or shamed. The series focused on two questions:

Who is responsible for leading a school district’s equity work and what roles can be played best by BIPOC and by white district leaders?

What skills and understandings about themselves and their systems do leaders need to develop?

Cross-Racial Learning

For BIPOC participants, two points emerged: They need shared and visible ownership of equity by white leaders (and associated coverage and support) and validation that their experiences of inequity are real. They described high rates of frustration and burnout when asked to lead deep cultural change around equity without the authority, support and respect of white leaders in their districts.

BIPOC often were asked to fix everything related to equity, extinguishing fires caused by anything cultural including racial slurs, complaints and missteps with individual education plans. Many felt they were on their own, with little or no coverage from their white superintendents (and for BIPOC superintendents in the group, from their mostly white school boards).

When defining coverage, participants shared these requests: ”Position me to be impactful by providing legitimacy to the equity role,” “Have difficult conversations with other district leaders about the importance of my role” and “See me as competent and partner with me as such.”

BIPOC leaders shared common experiences about the lack of recognition of the racial aggressions they routinely faced. “Why,” one wondered, “do many white superintendents seem to not understand these issues? Is it willful ignorance? How can they not see what is happening to us/me here?”

The need for coverage for BIPOC leaders highlights that equity work differs from other change initiatives. Many school communities and white leaders think equity work can only be successfully owned by people of color, even though the opposite is true. BIPOC leaders need true partnerships but have trouble finding them because many white superintendents who have skillfully led district improvement efforts in non-race-related areas become so unsure of themselves around work that they describe feeling “like deer in headlights.” White participants said they often deferred to BIPOC leaders — whom they saw as having more expertise — to take on much of the work involving diversity, equity and inclusion. Furthermore, they were not sure how or were unwilling to provide coverage and support when working with other white stakeholders.

Part of this hesitancy was because many participating superintendents had little knowledge and exposure to BIPOC and their experiences in schools and society. Raised in mostly white communities like the ones they often led, many had little contact with people of color as friends or education peers. In current relationships with BIPOC students, families and educators, many were authority figures who had not yet created enough trust for BIPOC to want to take the risks of speaking truth to their power. Some superintendents didn’t know how to, but others may not have wanted to. Truly taking in BIPOC perspectives might have disrupted their world view, shown them that they may have internalized more racism than they could stand and/or required them to develop skills and courage to take on institutional racism.

Moving Forward

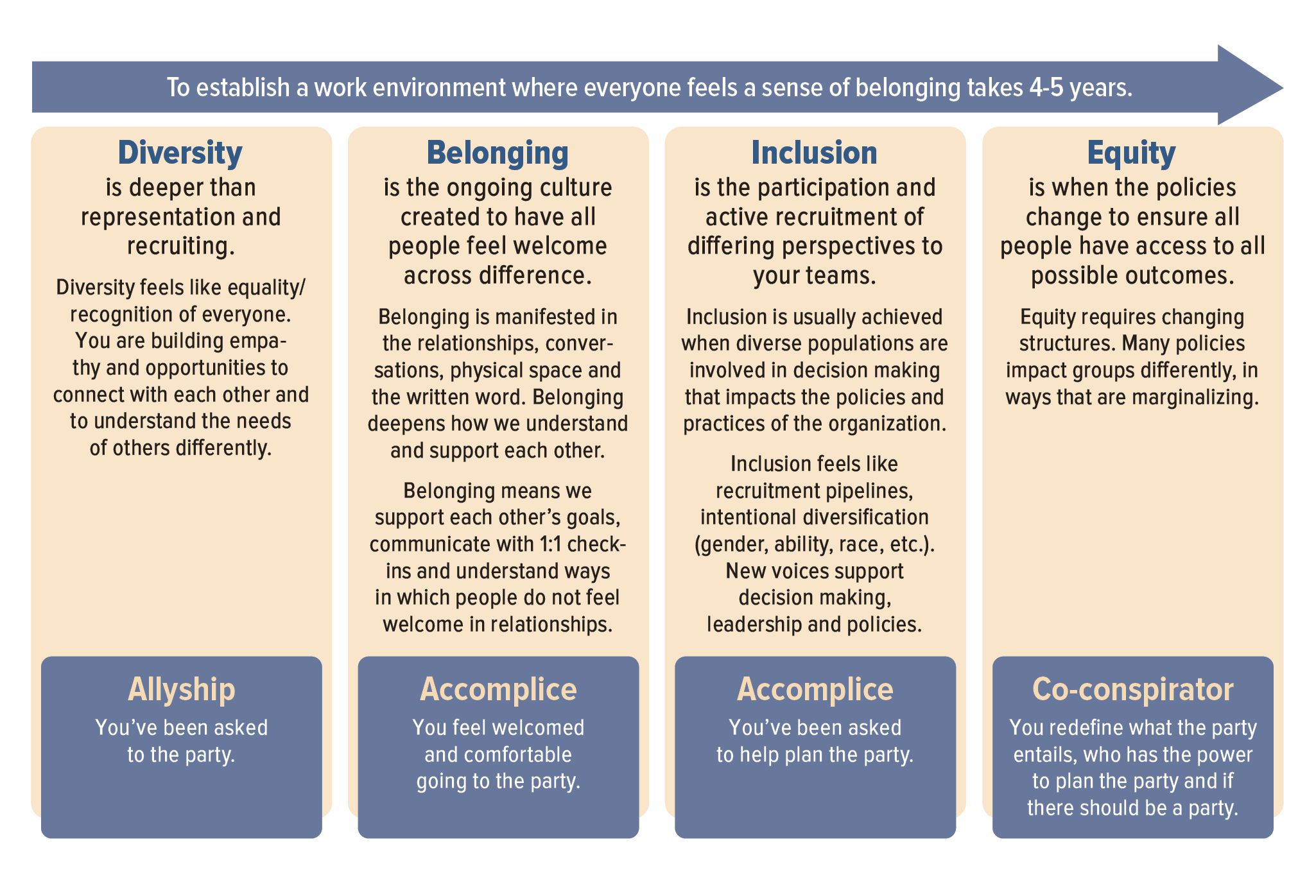

For many white and BIPOC participants, the workshop series was the first opportunity to have honest discussions across racial lines with peers about equity. They learned a great deal (as did we) about how to define and develop joint ownership of equity and how to do personal work on their own biases and triggers and use cross-racial spaces to build foundational knowledge and common, specific definitions of what “ownership” means in each setting.

Key learnings for whites included recognizing their power and privilege through white identity work. It meant owning the responsibility to lead this work and to not leave BIPOC leaders unsupported in taking on equity’s deep cultural changes. On this point, one superintendent said: “This is my work to do as a white woman in leadership. I cannot relegate this work to a DEI specialist, guest speaker or hired partner. Being silent and listening to the experience of BIPOC colleagues is required for my own learning, but using my voice to create the urgency and conditions for this work to happen in my district is needed. Academic excellence and social and emotional learning are equity work.”

In addition to healing and guided learning on combating felt aggression, BIPOC leaders got insight into tactical tools to drive equity change such as frameworks to identify equity in academic instruction and roadmaps for pacing. Empathy for cross-collaboration in the work also increased, particularly around what BIPOC described as “willful ignorance.” Said one participant: “It was tough, but completely understandable, to hear that my white colleagues sometimes don’t speak for fear of saying the wrong thing. We can’t promote this work in a cancel culture.” Another added: “There are white folks that are also passionate about this work and want change as much as I do. As they shared about their own challenges, I was able to understand better why some people don’t respond as quickly as I’d like. It’s not that they don’t believe in the work. It’s that they are dealing with their own personal challenges doing the work.”

Our own lessons address both content — needs for roadmaps, frameworks, cases and other teaching tools — and process — the power of building affinity and cross-racial containers. These lessons helped us work with colleagues from across Massachusetts during the past year to run a series of three day-long, in-person sessions to provide common language and experiences, five months of Zoom networking to provide customized paths for in-depth work and a capstone learning fair for 130 district leaders.

This is hard and messy work, yet doable. With commitments to shared ownership and to engaging in needed personal and system learning, school district leaders can develop schools where all students can learn at high levels, feel included, appreciate their own and other cultures, understand racism and work to dismantle it. n

Darnisa Amante-Jackson who is based in in Syracuse, N.Y., is CEO of The Disruptive Equity Education Project. Lee Teitel, founding director of a diversity and equity leadership project at the Harvard Graduate School of Education in Cambridge, Mass., is an education consultant.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement