Disruption in Action

October 01, 2019

From performance-based learning in agrarian central California to combating complacency in a Philadelphia suburb, educators leverage innovation systemwide

Like her colleagues in central California’s Lindsay Unified School District, Marla Ernest identifies herself as a “learning facilitator” — not a classroom teacher. If that sounds like a distinction without a difference, Ernest can assure you it is not. She sees her work today as vastly different from what she was doing when she started in the district 20 years ago.

“Very traditional, desks in rows, me in the front, direct instruction,” she says of those early days. “We had timelines, we had pacing guides and everything was curriculum-driven. We had these standards we had to teach, and if the learners didn’t catch up, they failed.”

Now Ernest’s students — scratch that, “learners” in Lindsay’s lexicon — sit at round tables, collaborating with others or working at their own pace on their own projects. They know exactly why they’re doing the work and where it’s taking them, Ernest says. As facilitator, she moves around the room, working with small groups or advising individuals on their own specific tasks.

For Ernest, who teaches English language development and drama at Lindsay High School, it’s a whole different world.

“It used to be really quiet in our classrooms because there was a teacher talking at the kids,” she says. “It’s pretty noisy now. There’s always conversations. It reminds me so much more of a workspace rather than ‘Everybody sit and listen to me.’”

That transformation is a microcosm of the dramatic and at times wrenching overhaul Lindsay schools have gone through over the past decade. The 4,100-student district, which has a 90 percent poverty rate and where nearly a third of students come from migrant families who work the surrounding citrus orchards, has transformed itself with a strategic use of technology and its own blend of performance-based, personalized learning. The results are impressive, with steadily rising achievement levels and a greatly improved school climate.

“I would never go back to the traditional system,” Ernest says.

Leveraging Disruption

Tom Arnett sees the work at Lindsay as an excellent example of how educators can leverage disruptive innovation to transform their schools. Arnett is a senior research fellow in education for the Boston-based Clayton Christensen Institute, which is named after the Harvard Business School professor and globally recognized authority who coined the term disruptive innovation.

Christensen described disruptive innovation as a process that expands access to valuable products and services. Disruptive innovations don’t immediately make an existing product or process better. Rather, they offer a new — and sometimes even “crummy” — version of a product, but one that is accessible to a wider and less-privileged customer base. Computers, for example, were once enormous and prohibitively expensive. The development of smaller but less-sophisticated devices broadened access dramatically. As the new products improved, they began to dominate the market.

Arnett acknowledges that schools don’t work like markets. They aren’t getting “disrupted” in that sense. Instead, they leverage disruptive innovations that provide schools with opportunities for wholesale change. The Lindsay schools, for example, use laptops, iPads and other technology not to improve the traditional school model, but to radically transform teaching, learning and student autonomy and engagement.

“They’ve made a major shift by using online learning as one of their key enabling elements to go to a competency-based education system,” Arnett says. “Not only has technology gotten better, but schools are figuring out better how to use the technology to rethink their instructional models, and now it’s coming more into the mainstream.”

Getting Personal

In other words, what makes Lindsay stand out is not the technology itself but the way it is used to upend traditional pedagogy and reach more children. The new model gives students agency over their learning — and frees teachers to develop personal relationships with them. Every learner in the district has a personalized learning plan, and each undergoes at least two formal conferences with their teachers each year — along with frequent informal chats — to discuss their particular academic plans and progress.

“You need to have this connectedness to learners,” explains Nikolaus Namba, who was director of 21st-century learning at Lindsay before leaving over the summer for the nonprofit Transcend Education. “You need to understand what works with this group of learners and then adjust your instruction to meet their needs rather than have their learning adjust to what you’re providing them.”

Ernest points to another key factor for how the school district has leveraged technology to boost student agency and buy-in. Learners can call up their personal academic goals and progress on a district portal and decide for themselves what areas they need to focus on next.

“There’s total transparency 24-7,” she says. “They always know where they stand and what they need to move forward.”

Compton’s Shake-Up

LaKeyshua Washington, principal of Davis Middle School in the 23,000-student Compton Unified School District in Los Angeles County, also is leveraging technological innovations — and any other tools she can think of — to spur student engagement. The school, which provides an iPad to each student, began to employ blended learning in its English, math and history classes last year and intends to expand the practice schoolwide. She says she is in the “early implementation stages” of adding project-based learning.

Bit by bit, Washington, who describes herself on her Twitter page as a “status quo disrupter” and “mediocrity opposer,” aims to change the culture of the school, transform teaching and create a learning environment that is based, above all, on engaging children. The steps are incremental, but she wants them to add up to something transformative. “Every year we’ve added a layer,” she says.

In her fifth year as principal, those layers range from low-tech to high — gradually replacing stultifying, literally old-school classrooms with what she calls “21st-century class-rooms” featuring colorful and comfortable furniture with distinct zones for small-group rotations, along with web cams and big-screen TVs for presentations.

The upgrade in décor is part of a much larger effort to transform the culture. Davis’ students overwhelmingly come from struggling, low-income families. More than half of in-coming students are two or three years behind academically, and growing numbers have mental health issues, she says.

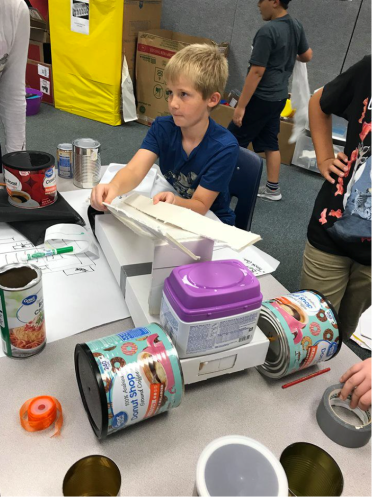

To increase engagement, Washington created an hourlong enrichment period once or twice a week — again blending low-tech with high. Students can choose from some 20 classes, from cooking and jewelry making to rocketry, electronics, photography, video production and animation. Teachers work alongside them, acting as facilitators and fellow learners.

Davis also has created a “breaker space,” where students take apart computers, appliances and toys and analyze how they work to complement the school’s “maker space.”

Washington says the richer enrichment has changed attitudes — and increased attendance. “When we have enrichment, the kids are running,” she says.

She expects the budding culture change to inspire teachers, too. “I’m hoping it kind of opens them up because people are stuck in more traditional ways of teaching and learning that are really counterproductive to the direction we’re moving,” she says.

Virginia’s Pilots

Amy Griffin, superintendent of the rural, 1,300-student Cumberland County Public Schools in central Virginia, is part of a network of nine school districts, along with the state education department and EdLeader21, working to overhaul the way students are assessed — and by extension, how they are taught.

The Cumberland system has designed and is implementing performance assessments from 2nd through 12th grade and is working with the network to develop student-led assessments — that is, student-initiated projects that demonstrate their learning.

This school year, in its own form of disruption, the district is putting in place performance-based assessments in high school history along with the traditional state-mandated end-of year exams to show the state legislature that the former can be just as effective — and better for both students and teachers.

“It’s decreasing rote memorization of material — drill and kill — and increasing more authentic work that has meaning to students,” says Griffin, now in her 10th year as Cumberland County superintendent. “It’s preparing them for their life, not just preparing them to do well on tests."

Griffin also is running pilot projects to experiment with student-led learning and assessment in hopes they will begin to transform teaching and learning across the district.

The most ambitious is Dukes Discover, a yearlong high school course debuting this fall in which students will develop their own “passion projects” in the community. They’ll conceive and design the project, implement it with guidance from a professional in the field and then present it to a panel of experts. If successful, they’ll earn a badge that will serve as a credential for potential employers and college admissions.

“My vision for that is that eventually every high school student will be able to earn digital badges at any time and work on these projects at any time,” Griffin says. “But we want to get it kind of perfected before we expand it.”

Seeking Dissatisfaction

Robert Copeland, superintendent of the affluent, high-performing Lower Merion School District in suburban Philadelphia, created a different kind of disruption after he took the helm in the district four years ago.

Copeland was aiming to keep the 8,700-student district out of complacency by bringing in an outsider who could take a deep look at its programs. He hired Kristina Paul, a Purdue University professor specializing in gifted and talented programming, as special assistant to the superintendent for program evaluation and data analysis.

Copeland says that while independent evaluators are common in larger districts, most smaller districts rely on their academic departments to do their own evaluations — which can never be a completely objective exercise.

“For a high-achieving suburban district, sort of making people play by the bureaucratic rules is disruptive and is saying to the organization on a fairly regular basis that somebody’s going to be holding the process accountable,” he says.

“I happen to believe that all effective change derives from dissatisfaction,” Copeland adds. “I don’t think anybody does anything differently if they’re satisfied with how they’re currently doing it. Part of what program evaluation should do is determine whether there’s a lack of dissatisfaction.”

Paul, whose first major assignment was to evaluate the district’s gifted and talented program, reports directly to Copeland and maintains an arm’s-length relationship with the departments she may be called on to evaluate. When she publicly presented her findings and recommendations, parents with children in the program were pleasantly surprised, Copeland says.

“They had come with the anticipation that somebody was going to sugarcoat, and she didn’t,” he says. “It was a frank assessment.”

Copeland says he could feel “anxiousness” among the departments in Lower Merion when he hired Paul, but that has dissipated. “We made it clear that, look, there’s nothing wrong with looking in the mirror,” he says. “We

can’t always look out the window.”

About the Author

Paul Riede is a freelance education writer in Syracuse, N.Y.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

.png?sfvrsn=3d584f2d_3)