Ending Old-School Nostalgia in Learning Spaces

October 01, 2017

Let’s start with the struggle between Bryan and his high school chair. Twisting and turning his hulking 6-foot frame in the metal chair in his high school history classroom, Bryan seeks a moment of comfort. He really wants to listen to his teacher, Mr. Mendez.

Directly in front of him sits 4-foot-8 Delores in an identical chair, her feet barely grazing the floor. In fact, every chair in this high school is standardized — like a hundred thousand others across the nation. If I were trying to design a life challenge to see if secondary students can pay attention and sit for 45-minute segments seven times a day without fidgeting, it would be “high school chair endurance.” Good luck, Bryan and Delores.

And this is only the tip of the iceberg. What about the room itself?

The classroom that Bryan, Delores and Mr. Mendez occupy is identical to every other classroom in the school. Same size, same shape, same rows of desks and chairs. The common descriptor is “self-contained classroom,” which connotes both confinement and sameness.

Down the hill at the feeder elementary school, the classroom space for a child in kindergarten is the same size as his big sister’s 5th-grade room, even though 5th graders are twice the size of 5-year-olds. This uniformity of space, based on nostalgic notions of the one-room schoolhouse, is stifling.

Positive Correlation

Any space we enter elicits physical, psychological and behavioral responses. When we arrive at a sports stadium, theater or library, we anticipate a specific type of activity will take place. The same is true in school settings. In a U.S. News & World Report article titled “A Swivel Chair: The Most Important Classroom Technology?” Allie Bidwell notes that research “shows intentionally designed classrooms are positively correlated to student engagement, which can in turn improve student success.”

It seems short-sighted to argue that a great teacher should be able to engage learners in any kind of space when we know that expansive and responsive learning environments stimulate such a wide range of possibilities. That is why, in recent years, there has been a surge of interest by educators, communities and architects in dynamically reimagining what school looks like. As in any other field, it’s time for our profession to step back and rethink old habits.

From striking new buildings to boldly designed spaces to modest changes within the four walls of a classroom, educators are defying our antiquated notions of school, creating physical spaces that match the needs of learners. In some cases, teachers and students even work with landscape architects to create magnificent exterior spaces that incorporate the surrounding land and facilities.

Innovative Design

Working with leadership teams at school sites across the country, I discover one constant — the inspiration that’s provided by innovation design teams. These teams lead the efforts to reimagine spaces, whether large scale or small. Composed of administrators, interested teachers, community members and students, these teams start by researching school modernization projects occurring nationally and internationally to inform potential upgrades to their own situation.

In November 2016, as part of the AASA Collaborative project, I made a site visit to Fremont School District 79 in Mundelein, Ill., to see firsthand their impressive classroom de-sign work, spanning elementary, middle and high school. (A short video of that visit, “Rethinking Education: A Personalized Learning Approach,” is available.) The efforts ranged widely, from bringing in flexible and comfortable furniture to remodeling and converting existing spaces to building dynamic new ones.

In Fremont School District, then-Superintendent Jill Gildea led an effort to reconceive the mission of the district and make corresponding changes to learning spaces with input from teachers, administrators and community members. Gildea says “students

were at the center” of the planning. At Fremont Middle School, students, known as “learning ninjas,” designed places for personalized learning in hallways, corners and vestibules. Former storage areas were converted into investigation

spaces. In collaboration with faculty and administration, a large media room was repurposed and renamed the Wildcat D.E.N. (Digital learning, Exploration and Networking).

Fresh Visions

Consider the impact of reimagining and converting an old library into the IDEA Center at Principia Upper School in St. Louis, Mo., which serves about 245 students in grades 9-12. Lead media specialist Diane Hammond points out “the change has been nothing less than transformative. The students choose to be here and the faculty look for opportunities to use our space.” The redesign provides spaces for collaborative investigation, panel dividers for student writing and drawing and unconventional seating arrangements.

Meanwhile, the fresh visions for learning spaces developed by the Rosan Bosch Studio in Copenhagen, Sweden, startle the imagination. Even if there is no possibility in the budget for design on this scale, I recommend that all educators examine images of the Vittra Telefonplan school and others like them and push past old-school notions of learning spaces.

Even an educator working alone can make a difference. In her widely circulated blogpost “Why the 21st Century Classroom May Remind You of Starbucks,” 2nd-grade teacher Kayla Delzer in West Fargo, N.D., shares the rethinking of her classroom: “Looking around my classroom, I quickly realized that I had far too much furniture, so I got rid of four tables, my huge teacher desk, 20 traditional chairs and a file cabinet. Next, I started looking for resources to redesign and repurpose what I already had. … What came out of that was flexible seating and open floor space. I thought about my students who would prefer to stretch out on the floor, and I purchased yoga mats and bath rugs for them to lay out on and work.”

Curricular Impact

Reviewing blueprints for new schools by the creative team at Fielding Nair International, my colleague Marie Alcock and I had an instructional epiphany when we observed the word classroom being replaced by new names for designated spaces. We developed this observation in our book Bold Moves for Schools: How We Create Remarkable Learning Environments (ASCD, 2017), where we show how curriculum planning strategies can be connected to such learning-space names as Da Vinci lab, portable green media space, global forum, Exploratorium, botanical pathway, R and D garage, innovation booth and seminar square.

Today, it’s possible for Mr. Mendez to expand Bryan’s menu of possible learning experiences to match the nature of the learning space. Bryan and a few classmates might create a short documentary in the portable green media space and share it with a school overseas in the global forum. Mr. Mendez might send a small group to join multiple teams from throughout the school who are diving into an issue-based discussion in seminar square.

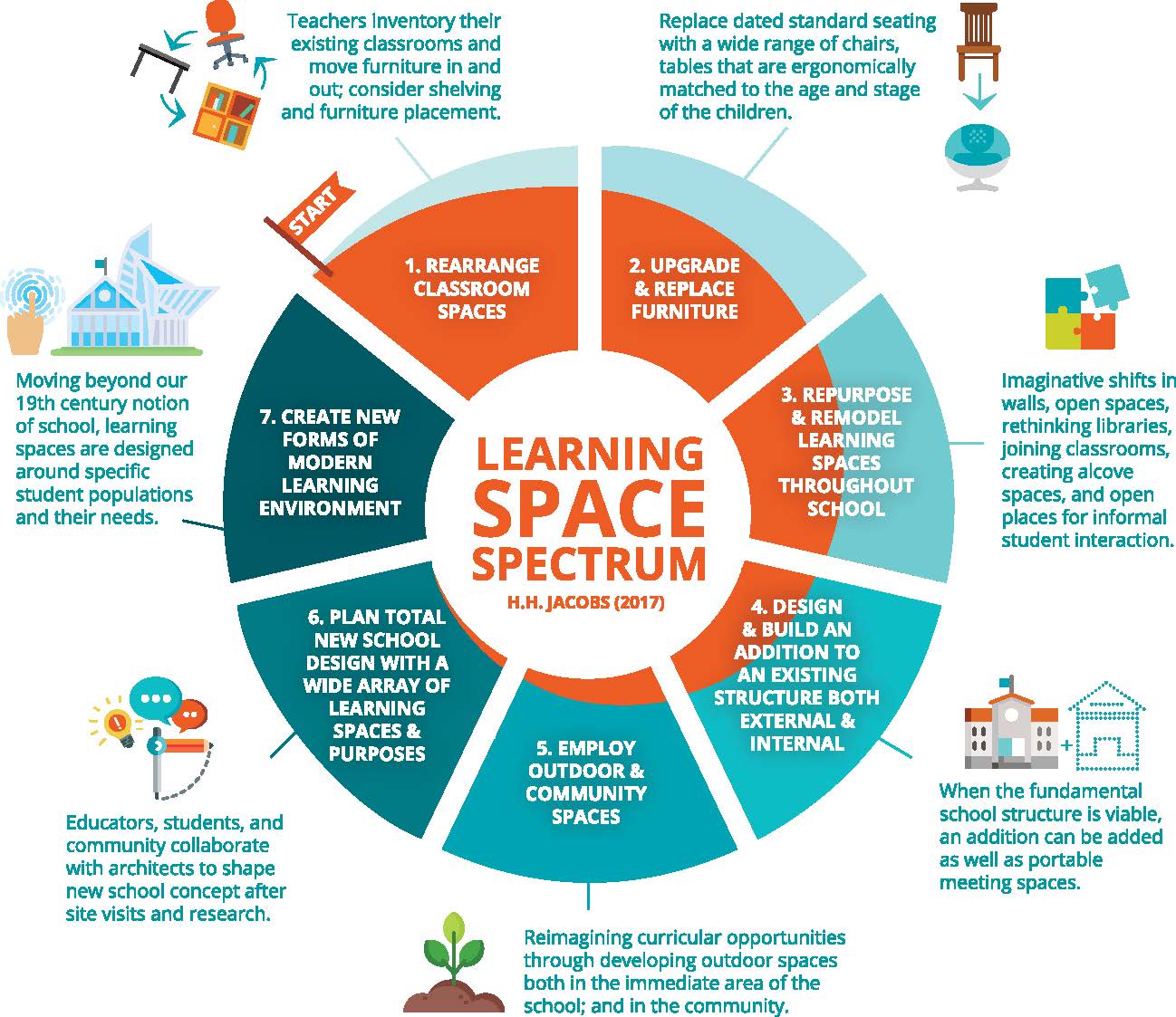

Space Spectrum

To assist innovation design teams, I created the Learning Space Spectrum. The spectrum shows how educators can begin with the most basic changes, such as moving furniture and fixtures to create a more accommodating environment. As you go around the spectrum, the options become increasingly complex, leading to dynamic new learning environments that, in turn, increase the opportunities for responsive and robust learning.

To be sure, engaging learning spaces are not enough to support the type of contemporary learning students need. In Bold Moves for Schools, we argue that to fully support learning, we must orchestrate four program structures — schedules, spaces, student grouping patterns and personnel configurations — and ask critical questions:

- What type of schedule best matches a specific learning experience?

- What type of space will enhance engagement?

- How should we group our learners and the adults who serve them to create long-term impact?

My experience working with school leaders is that the presentation of exciting new learning-space images ignites their imaginations and catalyzes them to take action.

Virtual Learning

I’ve focused on reimagining physical spaces, but educators also should recognize the challenges of refining learning designs for virtual spaces. Just as a wide array of physical spaces can support learning, there is no universal way to employ digital and multimedia learning environments.

Important differences exist between synchronous and asynchronous virtual experiences. The contemporary teacher needs to carry out tandem planning for both physical and virtual learning experiences. Fundamentally, a driving instructional question is this: What type of learning space, whether physical or virtual, will best serve our students for a specific goal or experience?

Author

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

-(16).png?sfvrsn=44688378_7)