Equitable Grading: Tales of Three Districts

May 01, 2019

How can educators more equitably and accurately report student achievement?

Grades are the most formalized way teachers report students’ academic progress, and they are the indicator that school districts rely on to ensure every student is on track to be college and work ready, regardless of background, culture or need. Other indicators used routinely by school districts — graduation and failure rates, retention and remedial course enrollment — are all defined by the grades students earn.

For school and district leaders, grades provide valuable feedback — evidence of achievement gaps, weaknesses in instruction and staffing and professional development needs. Perhaps no source of information more clearly reveals the quality of our schools’ and our district’s effectiveness than grades.

But for students and families, grades mean so much more. Grades can be a source of tremendous stress and anxiety. They determine everything from course placement and athletic eligibility to employment possibilities, college admission, scholarships and financial aid. Additionally, grades play a primary role in how adolescents shape their identities as learners and their life trajectories.

Variable and Inequitable

The irony is that while grades are vital to school improvement and to students’ futures, the teachers assigning those grades receive almost no training in how to grade effectively. Consequently, each teacher’s grading practices are different, often uninformed by research and usually based entirely on each teacher’s unique experiences and beliefs.

In some classrooms, tests are worth 40 percent of the grade, while in others 90 percent. Many teachers include criteria such as effort, participation, extra credit, group work or homework in a student’s grade, while others exclude some or all of these categories.

Because each teacher grades differently, a student’s grade can become more reflective of how the teacher grades than of the student’s academic performance. This uncomfortable fact should call into question the many decisions school and district leaders make about resource allocation and instructional improvement, all of which are based on grades.

Compounding the problem of variability in grading are the ways in which teachers, often unwittingly, use grading practices that are inequitable — mathematically unsound, biased and demotivating. For example, teachers often use mathematical scales and calculations that hide student growth and hamper students who struggle, and although teachers use grades to indicate how well students master course content, many also incorporate into grades whether students’ behavior or work habits gain their subjective, and often implicitly biased, approval.

Although most districts prioritize equity, and many teachers entered the profession to disrupt and reduce achievement disparities, traditional grading practices often perpetuate rather than eliminate disparities, rewarding students who have privileges and resources and punishing those without.

Most site leaders and district administrators know that teachers could benefit from instruction in how to grade but they are reluctant to broach the topic for fear of encroaching on teachers’ professional autonomy. Equally problematic, educators typically lack the language, resources, knowledge and courage to address the problem.

Avoiding the topic seems, at best, a concession that variable and unfair grading is a necessary byproduct of academic freedom and, at worst, a reluctant tolerance of the damaging impact of current grading on our students, particularly those who are most vulnerable.

Five years ago, after I left my position as director of curriculum for a 35,000-student district in California, I investigated the research on grading and found classroom educators who were grading differently. With this knowledge, I began working with schools and districts to help educators recognize the damaging and inequitable impact of many traditional grading practices and to facilitate a process in which teachers and leaders explore more mathematically sound and less biased and subjective approaches to grading that build student motivation and stamina.

Over time, these school districts systematically revamped their grading practices, resulting in significant reduction of achievement gaps and leveraging the process to strengthen teaching and learning.

Re-imagining Grades

A few miles from San Francisco is San Leandro Unified School District, a racially diverse district where nearly two-thirds of students are low-income. The district is comprised of eight elementary schools, two middle schools and a comprehensive high school.

Placer Union High School District, 125 miles to the north, is a smaller, suburban/rural district with four comprehensive high schools and one alternative high school.

Each district recognized that to equitably implement course standards, they needed to re-imagine how to assess students and report achievement. Jeff Tooker, deputy superintendent of educational services in Placer, put his district’s challenge this way: “Students become intrinsically motivated and develop a growth mindset to achieve higher standards when their grades are equitable and accurately measure where they are in the learning process.”

Both Placer with its 4,000 students and San Leandro with 9,000 students had the goal of improving the grading of student work, but each took a slightly distinct path. The districts began the work by ensuring that leaders at all levels understood the urgent need and benefits of equitable grading.

In San Leandro, district leaders hosted a workshop/strategy session for middle and high school administrators to build interest and commitment to this initiative. In Placer, the district held a closed study session on equitable grading with its board of trustees to gain approval and build a “tailwind” for launching the work.

Each district knew that changing grading policies “from the top down” would create confusion

and backlash among teachers. Therefore, district leaders chose to leverage teachers’ professional expertise, creativity and commitment to students.

Piloting Practices

Implementation in both districts began with a pilot cohort of teachers — some of whom were teacher-leaders, such as department chairs, or who were simply excited to try something new.

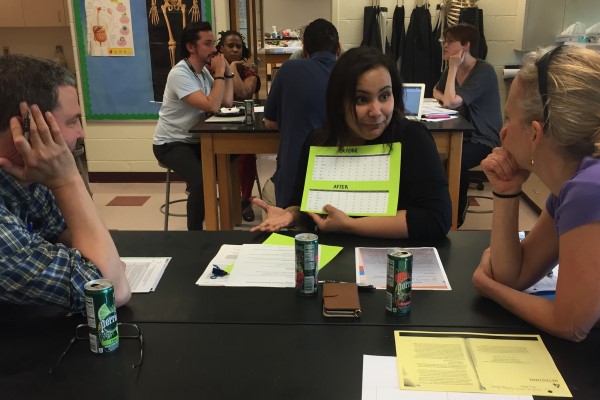

In each district, pilot teachers participated in a two-day intensive workshop to learn how common grading practices date back to the Industrial Revolution and reflect outdated values and debunked assumptions. They also learned about the research and strategies to implement improved grading that is more accurate, resistant to our implicit and institutional biases, and motivational.

In San Leandro, instructional coaches attended workshops alongside teachers, while in Placer, site administrators participated with their teachers.

The cohorts learned about more equitable grading practices, which included employing a 0-4 point scale rather than a 0-100 percentage range, incorporating retakes and re-dos and excluding common grading criteria such as effort and participation that are highly susceptible to implicit and institutional biases.

Positive Movement

Teachers in both districts piloted these practices and observed results within a structured series of action research cycles. After a year, the responses from each district’s pilot cohort were overwhelmingly positive — not only because of their collective evidence of the benefits of these practices, but also because of the empowering design of the professional development.

For two more years, the districts enrolled additional cohorts of teachers, gradually generating a critical mass of teachers who were experienced and could testify to the powerful impact of the more equitable grading practices. Despite their vastly different contexts, teachers in both districts reported that the new practices improved their effectiveness, increased student motivation and transformed learning.

Specifically, the districts found:

The percentage of students receiving D’s and F’s decreased — and decreased more dramatically for students of color and for students with special needs. In San Leandro, the reduction in D/F rates among a single cohort of teachers equated to approximately 250 fewer failing grades, which meant the district could reallocate the cost of what would otherwise have been 250 remedial “seats” to other instructional needs.

Grade inflation, as measured by the rate of students receiving A’s, decreased, and they dropped more dramatically among more privileged student populations. In Placer, students who did not qualify for free or reduced-price lunch had a sharper decrease in A’s, reflecting how traditional grading practices disproportionately benefit students with re-sources because of the inequitable inclusion of extra credit and other resource-dependent grading criteria.

Students’ grades didn’t just improve; they were more accurate. Improved grading practices significantly decreased the difference between students’ grades and their scores on standardized assessments of that content, and the effect was stronger and more likely for students who qualified for free or reduced-price lunch.

Students and teachers reported less stressful classrooms and stronger teacher-student relationships. Learning and implementing these practices enhanced teachers’ work as professional educators. In Placer, nearly half the teachers this year reported that participating in this professional development made them more likely to stay in the district.

Leader Led

Although teacher-led change is leading to districtwide improvement in these two districts, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach to positive change in grading practices. In Windsor Locks Public Schools in Connecticut, the district administration adopted a strong leadership role from the outset.

In 2013, the district, led at the time by Superintendent Susan Bell, declared that the graduating class of 2020 would have a “mastery-based” diploma. Toward that goal, staff at every level had a role. Teachers would develop standards for each course while site administrators would ensure that teachers had resources and time to collaborate.

The district launched a public campaign to educate families and the community about the initiative and the implications for changing grading practices. Bell wrote a series of newsletter articles for the district website and local newspaper.

Making the conversation so public created challenges, however. Parents were familiar and comfortable with traditional grading despite its inequities (and some had likely benefited from these very inequities) or were anxious and resistant to altering grading.

In response, Windsor Lock district leaders and the school board have made slight concessions to their report cards, but they continue to educate and advocate for the benefits — both pedagogical and equitable — of more significant improvements to student grading.

Opening Doors

These districts’ headway with correcting traditional grading practices gives us hope. In our constant commitment to improve student achievement, we can adopt new curriculum, celebrate holidays of more cultures and train teachers in new instructional strategies, but it’s the course grades of students that open doors or close them.

If our grading practices don’t change, the achievement and opportunity gaps will remain for our most vulnerable students. If we are truly dedicated to equity, we have to stop avoiding the sensitive issue of grading and embrace it.

About the Author

Joe Feldman is president and CEO of Crescendo Education Group in Oakland, Calif. He is the author of Grading for Equity: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How It Can Transform Schools and Classrooms.

Equitable Grading Practices

Joe Feldman, who leads the Equitable Grading Project at the Crescendo Education Group, suggests several grading practices that teachers have found to be more accurate, bias resistant and motivational than traditional forms of grading.

GREATER ACCURACY

Grades on a 0-4 scale.

Grades weighting more recent performance.

Grades based on an individual’s achievement, not the group’s work.

BIAS-RESISTANT

Grades based on required content, not extra credit.

Grades that exclude participation and effort.

Grades based on summative assessments, not formative assessments.

MOTIVATIONAL

Use of retakes and redos.

Use of rubrics.

Feldman elaborates on these in his book Grading for Equity: What It Is, Why It Matters, and How It Can Transform Schools and Classrooms (Corwin).

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement