Mini-Observations: A Keystone Habit

December 01, 2017

In his 2012 book, The Power of Habit, Charles Duhigg, a New York Times journalist, explains the “keystone habit” — a simple routine that has a surprisingly large impact on people’s lives.

Two examples: When families eat dinner together, the children develop better homework skills, get higher grades, display greater emotional control and are more self-confident. And regular exercise makes people more productive, less stressed, more careful with nutrition, smoking and credit card use and more patient with others.

It turns out there’s a keystone habit in schools: Principals making short, frequent, unannounced classroom visits, each followed by a face-to-face coaching conversation.

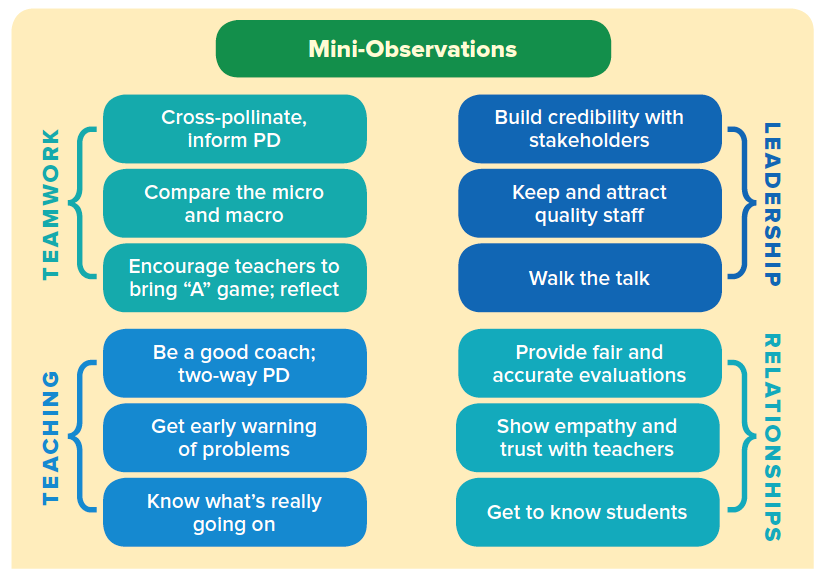

This simple practice has an outsize impact on teaching, relationships, collaboration and leadership, four of the most effective ways to improve student learning. As a former principal (Kim) and a veteran teacher (Dave), we have both experienced the ripple effects of mini-observations in each area:

Continuously Improving Teaching

With mini-observations, principals:

- See what’s really happening in classrooms. When they make one or two 10- to 15-minute classroom visits a day and talk to teachers afterward, supervisors develop a much better sense of the day-to-day quality of teaching than with traditional evaluations or superficial walkthroughs. Knowing daily teaching is the foundation for effective praise, coaching and professional development.

- Get early warning of classroom problems. Supervisors can nip ineffective teaching practices in the bud by spotting and addressing them early in the school year.

- Provide focused coaching. After traditional formal evaluations, teachers are often overwhelmed by multiple criticisms and suggestions. Principals should focus on one “leverage point” with each mini-observation, spreading suggestions over 10 or so visits throughout the school year.

Building Relationships with Teachers and Students

With mini-observations, principals:

- See kids in their element. During mini-observations, supervisors can look over students’ shoulders, talk with them about what they’re learning and gauge how they’re experiencing school. When principals escape their offices for these classroom glimpses, supplemented by chats in corridors, cafeteria, playground and bus lines, it makes them more insightful instructional leaders and helps them forge authentic connections.

- Build empathy and trust. Low-stakes chats with teachers about short observations give supervisors a better understanding of what teachers face every day, from technology glitches to challenging students. Researchers in Chicago have found that relational trust is one of the hallmarks of effective schools, and quick post-visit conversations are an ideal way to develop that bond. Savvy supervisors approach these talks with curiosity and humility and put the teacher at ease by conducting them in the teacher’s classroom when students are not there.

- Write fair end-of-year evaluations. One of the surest ways for administrators to undermine a teacher’s trust is writing an unfair or clueless evaluation. By doing numerous in-formal observations, debriefing with the teacher after each one, reviewing the teacher’s self-assessment and periodically visiting teacher meetings, supervisors continuously build their knowledge of each teacher’s work, making their year-end evaluation far richer and more accurate.

Encouraging Teacher Collaboration and Reflection

With mini-observations, principals:

- Cross-pollinate effective teaching practices. One of the delights of making regular visits to classrooms is witnessing effective teaching practices and students’ “aha!” moments. Seeing these gems allows administrators to give teachers detailed, authentic praise and spread practical ideas to colleagues and teacher teams. Principals also can encourage teachers to share ideas in faculty meetings, conferences and professional journals.

- Connect lessons to the bigger picture. Teacher teams preparing curriculum units and discussing assessment results is one of the most important drivers of effective instruction. Making frequent classroom visits lets supervisors see how this outside-the-classroom work plays out in practice — and how teachers’ insights into student errors and misunderstandings inform daily teaching.

By knowing the work of teacher teams, says Paul Bambrick-Santoyo, author of Leverage Leadership, supervisors feel like they’re wearing 3-D glasses when they walk into classrooms. Armed with a deeper understanding of classroom instruction, they can make more valuable contributions when they visit teacher team meetings.

- Encourage teacher reflection. Frequent unannounced visits carry the implicit message that teachers should bring their “A game” every day — and gets them thinking about what their A game is and how it can be continuously improved. Some teachers may find this daunting at first, but the follow-up chats give teachers a chance to explain bad mo-ments (We got no sleep last night because our daughter has the flu), and frequent visits put the inevitable stumbles in perspective.

With a climate of trust and support, teachers realize all they need to do is teach. The supervisor will drop in every few weeks to take a snapshot, and they will have a chance afterward to reflect on what happened — all of which is less stressful than preparing an annual “glamorized” lesson that might not go well. For supervisors, it’s a huge relief not having to write lengthy evaluations and make a comprehensive, high-stakes judgment based on a single visit that might not accurately represent typical performance.

Demonstrating Leadership

With mini-observations, principals:

- Walk the talk. How administrators spend time reflects their core values. Dwight Eisenhower used to say, “What is important is seldom urgent, and what is urgent is seldom important.”

It’s easy for principals to be chained to their desks all day responding to e-mails and lower-priority issues. Getting out of the office and doing one or two mini-observations directly advances the school’s fundamental work, and each takes only 30 minutes, including the visit, chat and a brief follow-up summary. Is anything more important? A principal who can’t squeeze in at least one mini-observation most days has a serious time management problem.

- Foster teacher efficacy. Frequent, substantive conversations with teachers help them see how their work fits into the school’s mission, which makes them less likely to leave for greener pastures. In addition, the school’s reputation for positive professional working conditions attracts high-quality educators. Everyone wants to be part of a dynamic and collaborative team.

- Master the job. Supervisors who make regular classroom visits and follow up with teachers know the inner workings of their school. This builds credibility with faculty, parents, superiors and other stakeholders. It’s always winning to tell a mother about a thoughtful comment her son made in class, to describe a funny teacher-student interaction in a faculty meeting or to give the superintendent specifics on how to tweak the new laptop program. And if an unhinged parent unfairly attacks a teacher, the principal can defend him or her with on-the-ground evidence from the frequent classroom observations.

The Payoff

All told, the keystone habit of mini-observations produces no fewer than 12 benefits in teaching, relationships, collaboration and leadership. That’s a serious return from only 30-60 minutes a day!

In The Power of Habit, Duhigg describes the benefits of keystone habits, all of which apply to short classroom visits. He says they:

- encourage change by creating structures that help other people thrive.

- cause small ripples that produce larger, transformative changes. “A series of small wins,” says Duhigg, “can leverage modest advantages into patterns that convince people that larger achievements are possible. Small wins convert cumulative successes into routines.”

- “[can] create a new organizational culture that embodies new values,” he says. “Particularly during times of uncertainty, a new culture can transform behaviors and make decision making an automatic outgrowth of an organization’s values.

Of course, not every mini-observation and follow-up conversation is a home run. Many supervisors need practice honing their observation and feedback skills. Teachers sometimes are defensive and unreceptive, and there are days when administrators are so swamped with paperwork, meetings and discipline referrals that they don’t visit a single classroom.

Duhigg’s response: “[S]uccess doesn’t depend on getting every single thing right, but instead relies on identifying a few key priorities and fashioning them into powerful levers. … The habits that matter most are the ones that, when they start to shift, dislodge and remake other patterns.”

That’s the potential of short observations to bring about transformative changes in teaching, relationships, collaboration and leadership. Policymakers should give serious thought to shifting from the traditional teacher-evaluation model, which focuses mostly on compliance and has a remarkably weak track record, to mini-observations. Principals, teachers and students will reap significant rewards.

About the Authors

Kim Marshall, a former principal in Boston, is a school leadership consultant in Brookline, Mass., and publisher of the Marshall Memo. E-mail: kim.marshall48@gmail.com. Dave Marshall is a history teacher at University Prep in Seattle, Wash.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement