Parenting in the Public Eye

January 01, 2025

When School Administrator put out a call last year to hear from superintendents whose children attend or previously attended the schools in the same community, we heard from quite an array. Many of them openly shared how that experience played out for them and their sons and daughters.

A small sampling of their observations:

A small-city superintendent (male) in Massachusetts: “I have 9-year-old twins, and I am sure this job has an effect on them.”

A suburban superintendent in New England (female): “My children know they can’t expect me to be at home every night and will preemptively ask me if I am available. I am not sure if other families have a schedule that permits their own children to assume that their parent will be around for all evening functions, but my children do not make that assumption. They are used to eating late or coming with me into the office as needed if something comes up.”

A former superintendent (female) near Madison, Wis., with three children: “Oftentimes, I thought my children paid a bigger price with all of the scrutiny they faced.”

A rural superintendent (male) in Massachusetts: “When my kids were younger, they did not like knowing I was in their schools visiting, and in some cases, would ask to see the nurse or use the restroom if I visited their class. My oldest has come around, while my youngest — not so much.”

The number of superintendents who have school-age children largely is an open question. One of the only surveys to explore this subject is the periodic Snapshot of the Superintendency run by the New York State Council of School Superintendents. In its 2020 study, NYSCOSS reported 45 percent of the state’s superintendents had school-age children. Only 19 percent attended school in the district, a sharp drop from the 46 percent in 2015 whose children attended class in the superintendent’s district.

Four of the veteran superintendents we reached out to — Dan Bittman of Elk River, Minn.; LaTonya Goffney of Houston, Texas; Terry Ward of Baldwinsville, N.Y.; and Marie Wiles of Guilderland, N.Y. — prepared short essays on sundry aspects of the parenting life they’ve experienced.

Jay Goldman is editor of School Administrator magazine.

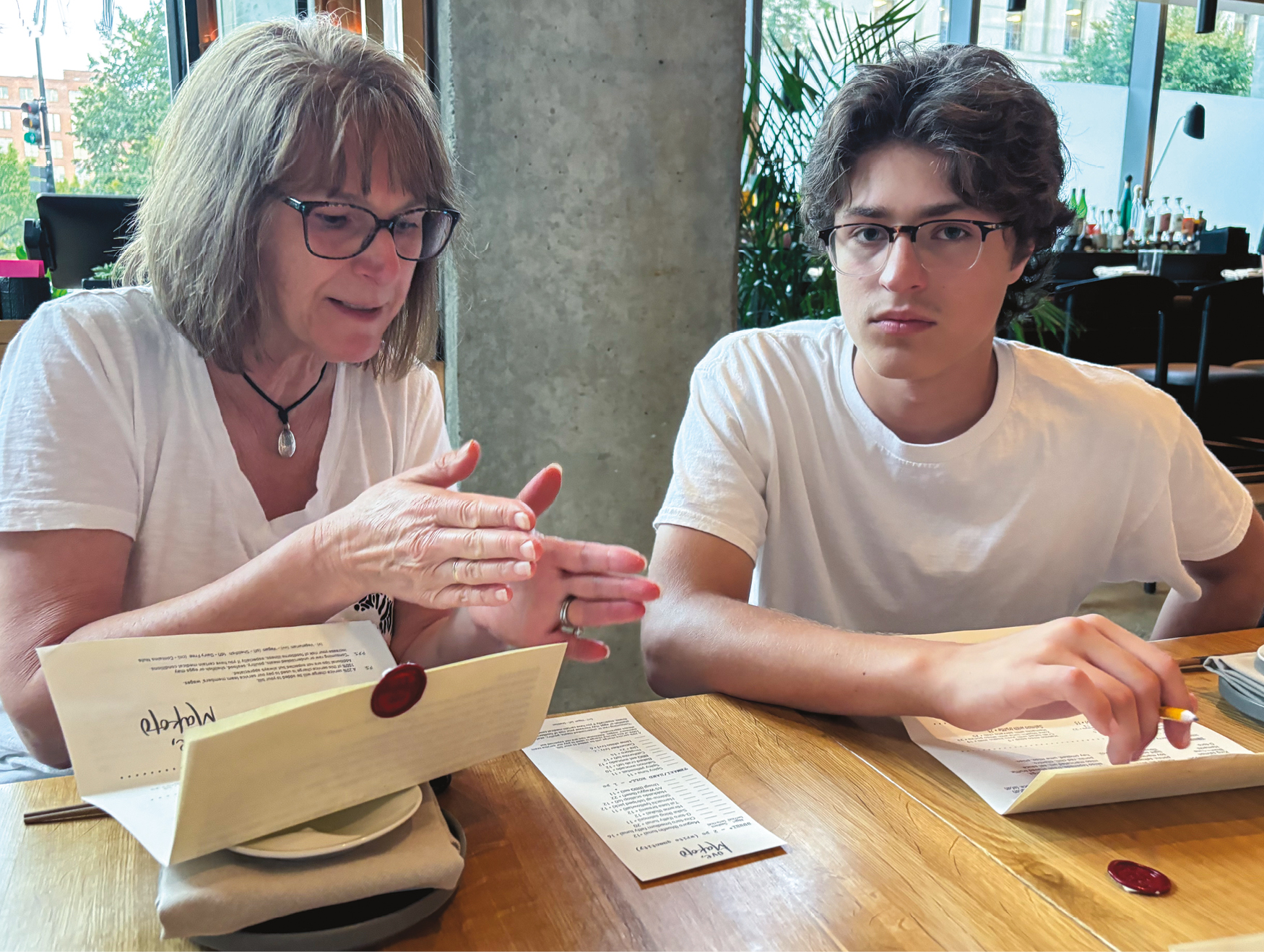

By Marie Wiles

Being the parent and superintendent of a child who attends your school district is a bit like a tale of two cities. It can be the best of times and the worst of times. I’ll start with the worst.

My suburban school district closed its summer leadership retreat in 2021 with a burn barrel. Each of our 28 administrators brought an artifact from their experience during 2020-21, a school year upended by the COVID-19 pandemic. They told the story of their chosen item and then watched it go up in flames. The activity was cathartic.

I burned my son’s 8th-grade report card. It was that bad.

A Trying Year

Ben is our only child. My husband and I like to joke he was born when my biological clock was on “snooze” (I was 44), so we count our blessings every day we have him. He has been a student in my school district his entire life. I always have tried to be mindful of giving him and his teachers plenty of space, knowing just how awkward it can be to have the superintendent’s child in your class.

During that crazy COVID year, our 8th graders were housed in the high school rather than the middle school, alternated days between virtual and in-person learning and started school at 10 a.m. to accommodate our five tiers of transportation. This plan was designed with social distancing, not adolescent development, in mind.

Like many of his peers, Ben lost his way in the chaos. What hurt the most was that I was almost completely unavailable to him, consumed with what seemed like a 24/7 COVID response. It was an extreme case of work/life imbalance. Ben paid the price.

On the other hand, some things make being the superintendent’s kid pretty cool, such as getting the chance to tag along with me (and his dad, the director of a public library) to visit our congressman in his Washington, D.C., office. I was there as an AASA Governing Board member. We spent 45 minutes chatting with Rep. Paul Tonko, D-N.Y., who was delighted to speak with one of his younger constituents. Nine-year-old Ben loved it.

But Ben would not likely give these examples of how my job has affected his life. His “worst of times” are day-to-day realities, such as the barrage of questions he gets when there is a possibility of a snow day or his embarrassment when I share a story with the entire staff about something we did over summer vacation. He has told me more than once that he wishes he could experience high school “like everybody else.”

Beyond Anxieties

Ben’s “best of times” are also rather mundane. One day during his junior year, he spotted me in the lobby of our high school during passing time, talking with the principal. The lobby was filled to capacity with students trying to connect with their friends for a few precious seconds before hustling off to their next class.

To my complete surprise, Ben came up to talk with me in the midst of all of this, just to say hello and ask how my day was going. Later that night he said, “Seeing you today was the best part of my day. It is awesome to get to see you.” It was the best part of my day too!

Ben, now 17, is a senior this year. He recently told me he is “over” the anxiety of being the son of the superintendent and eager to enjoy his last year of high school. I look forward to handing him his diploma in June. No burn barrel needed.

Marie Wiles is the superintendent of Guilderland Central School District in Guilderland, N.Y.

By Terry L. Ward

I became the superintendent of a small, rural district in upstate New York in January 2018. Later that year, my board of education adopted policy 7552, which guarantees our students who are dealing with their gender identity certain rights and protections.

The adoption of this policy satisfied federal and state laws around the protection of transgender students. The school board’s action came with some parental concerns, particularly over student bathroom usage. As a community, we have come a long way in understanding and supporting gender non-confirming students.

At the time, I did not realize I would be personally appreciative of the supportive policy and practices.

Parenting Fears

Serving as a superintendent of the 870-student Cato-Meridian schools has been an awesome experience. On a daily basis, I am privileged to work with students, their families and a highly dedicated staff.

As much as I love my job, my most important role is being the dad of three wonderful school-aged kids. My wife, who is a speech-language pathologist, and I have a combined 55 years of experience in K-12 education. We have three children: Sadie (16), Lindy (14) and Anson (12). They attend school in the neighboring district, a suburb of Syracuse.

Over the last five years, both school districts began using a social-emotional screening tool called the BIMAS. The Behavior Intervention Monitoring Assessment System measures behavioral functioning and social-emotional skills in children. My kids’ school district began using the BIMAS in 2017. Cato-Meridian began using it in 2021.

During the 2017-18 school year, Lindy’s 2nd-grade teacher asked us for a parent-teacher conference. Even as experienced educators, my wife and I were a bit apprehensive. During our meeting, the teacher explained Lindy was telling other 2nd graders in the class that she was a transgender boy. The teacher was extremely supportive but thought we should know about the conversations.

Post-pandemic, we received another phone call from the school district. It was Sadie’s school counselor calling to tell us the answer to item 24 on the BIMAS. My heart immediately dropped as a dad because I knew Item 24 was the question about suicidal ideations. Immediately, my wife and I put a team together to get help for our oldest child.

As parents, we had tremendous guilt because we never knew Sadie was struggling. She had good grades, was involved in sports and drama productions and had many friends at school. Our many years of working with kids professionally did not help us identify any problems our daughter was experiencing.

Life-Affirming Tool

Thankfully, today we are in a much better place due to a multitude of supports for my daughter. Sadie is a thriving teenager midway through senior year of high school and has plans to become an emergency room doctor. Recently, she spoke at the annual spring conference of the New York State Council of School Superintendents to advocate for school districts to implement a social-emotional screening tool.

Back in 2018 as a new superintendent, I worked with my district to adopt a transgender policy. I had no idea it would have a personal impact on me years later with Sadie and Lindy. Sadie was struggling with her identity, leading to the alarming response to item 24 on the BIMAS. I’m glad someone asked about her thoughts, even if it was just a screening tool. Who knows where, as parents, we would be without that social-emotional screening tool. We are a thriving family of five today, just trying to figure out life.

Terry Ward moves this month from superintendent of Cato-Meridian Central Schools in Cato, N.Y., to superintendent of North Syracuse School District in North Syracuse, N.Y.

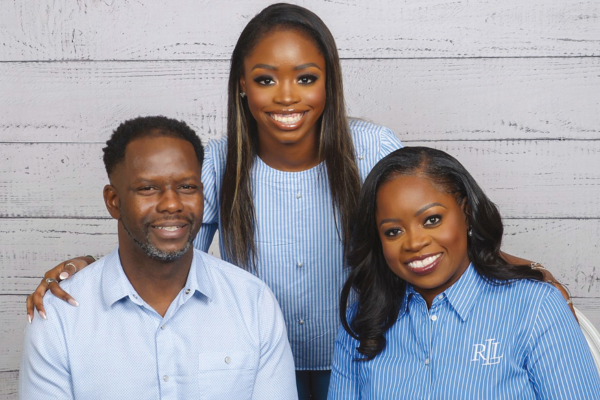

By LaTonya Goffney

I've only missed one board of Education meeting since becoming a superintendent in 2008. If you do back-of-the-envelope math, that is two meetings per month for the 16 years I’ve been in the seat — 384 meetings. That doesn’t include board workshops, special meetings or other board gatherings.

I’d say those are good attendance odds. My track record of being present is solid. I’ve been lucky enough to be present for them all.

Until February 15, 2022.

My daughter’s varsity basketball team was set to play in the first round of the Texas state playoffs. She was a senior and, given the powerhouse opponent, everyone expected this would be their last game — and her last game. I had to decide: attend my daughter’s final basketball game or miss a board study session.

The Elusive Balance

As the superintendent of three school districts over 16 years, I’ve missed my fair share of events. I’ve had to say no to dinners with friends and pass on family affairs and girlfriend trips. I’ve skipped more than a few nights of tucking my daughter in and picked up plenty of fast food rather than cooking dinner. I’ve skipped Saturday brunch, and all of my Friday nights were spent cheering on high school athletes from the sidelines of football fields and basketball courts.

While not always happy, my family understood the challenge of being the leader of a school district. My husband Joseph and daughter Joslyn have been my rocks, and I have leaned on them more times than I can count.

On February 15, 2022, I missed my first board meeting.

While I knew I needed more balance, I never felt the need to apologize or justify my passion for being a superintendent. I tell anyone who asks that I am living the dream. If you know my past, you know I am doing what I love.

Many working wives and mothers experience “wife guilt” and “mom guilt,” and I get it. I do, too. But as a woman and a mother to a daughter, I want her to know that chasing your dream can go hand in hand with having a family. No, there’s not always balance — you’re always striving for that. And it’s not easy. But nothing worthwhile is ever easy.

Instilling Lessons

And so, throughout my journey, I’ve let my daughter Joslyn see me struggle and fail, struggle and succeed. So long as she takes away a few things from her observations:

It’s OK to be ambitious. Ambition is not a bad word.

Life will never be perfectly balanced. Accept that life is messy, and sometimes there is no balance or compartmentalizing. Sometimes, you just do your best, and that will be OK.

It’s acceptable to not be perfect and not have all the answers.

You can have it all — family, career, friends — as long as you keep the main thing the main thing.

At the end of the day, it’s about having the resilience to get back up and work through life’s challenges. I feel I’ve instilled in my daughter, now 20, through my example of service to others, this lesson and many more. Having the grit and determination to show up is half the battle.

LaTonya Goffney is superintendent of Aldine Independent School District in Houston, Texas.

By Daniel T. Bittman

The decision for superintendents to live within or outside the school districts they lead is multifaceted, impacting both personal and professional lives, as well as the experiences of their school-age children.

Over the past 15 years, I have led two school districts in Minnesota — one where my children attended and one where they did not. I discovered advantages and disadvantages to both living arrangements, especially regarding the impact our residency had on my three children.

School board members everywhere generally want a superintendent to reside in the district, be actively involved in the community and raise children there.

Living within the school district demonstrates commitment, builds a deeper connection with the community and enhances accessibility to stakeholders. A superintendent who is also a resident may have a stronger vested interest in the community’s success, ideally strengthening trust and collaboration between the superintendent and the community’s residents.

However, the landscape for superintendents is changing rapidly, resulting in more stress, higher turnover and greater challenges to balancing professional duties and personal life.

Heightened Scrutiny

Having my children attend school in one district I led and then in schools outside a district I led presented unique opportunities and challenges for them and for me.

Disadvantages of Living Outside the District

Perceived lack of commitment. Living outside the district can be perceived as a lack of a visible, top leader’s commitment to the community. It might lead to questions about the superintendent’s investment in the district’s success and could erode trust among community members over time.

Reduced community presence. Superintendents living in the district more easily can attend community events, school functions and athletic events. Their presence can reinforce their role as a community leader, so living beyond the district can limit these opportunities.

Potential for conflict. If a superintendent’s children attend schools in a neighboring district, community members might question the superintendent’s confidence in his or her own district. It also might lead to accusations of favoritism, especially if funding or program development seems to favor the other district. Finally, living in the district might blur the lines between personal and professional life with community members expecting constant availability outside of work hours.

When my children attended schools in the Sauk Rapids-Rice School District, a rural district in central Minnesota, I experienced a stronger connection with the community. Their school experiences gave me firsthand insights into the schools’ strengths and weaknesses. But it also subjected my family and my young children to heightened scrutiny and expectations. Community members always knew their successes, failures and daily experiences would be reported or highlighted to me and others, and my wife and children faced criticism and felt tension over decisions the school board and I made, such as difficult budget cuts and contract negotiations with the teachers’ union.

I found it nearly impossible to be “present” with my family, to be a dad rather than the superintendent or to live authentically without outside scrutiny.

Conversely, when my children attended a different district from the one I was leading, it allowed them to benefit from programs that better suited their needs, provided stability in their lives when I moved to a new district and allowed them to figure out who they were without being under the microscope.

Advantages of Living Outside the District

Access to better or different schools and programming for our kids. Superintendents might choose to live beyond the district to provide their children with better or different educational opportunities. If neighboring schools offer superior programs, extracurricular activities or overall educational quality, it can be a compelling reason to locate one’s residency there.

Separation of roles. Living outside the district can help superintendents maintain a clearer separation between their professional and personal lives. This distinction can reduce the pressure and scrutiny they and their families might face from being constantly under the community’s eye.

Personal and family considerations. Family needs and preferences significantly influence this decision. Proximity to extended family, availability of specific health services or lifestyle preferences can make living outside the district more attractive.

Attending schools apart from those I was leading also gave them more quality time with their siblings and parents without continuous interruptions from community members. When I got home from work, I could better disconnect and be present. Occasionally, however, it led to perceptions of divided loyalties, questions from the board or community members about why the district wasn’t “good enough” for the superintendent’s children and worries that I would not stick around. Over time, my board members recognized my commitment to the district, my visibility throughout the community and my constant accessibility to those I served and supported.

A Personal Decision

The residency decision for a superintendent is deeply personal. It involves weighing professional expectations against personal and family needs. Superintendents must carefully consider the various factors and choose what best balances their professional responsibilities with their family’s well-being. My children’s different experiences ultimately made us all better, more prepared and closer as a family.

Daniel Bittman is superintendent of Independent School District 728 in Elk River, Minn.

Author

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

.png?sfvrsn=3d584f2d_3)