Reversing a Downward Spiral

November 01, 2021

A former superintendent guides the restart of an urban school by building up three legs of success

Plans interrupted.

At 38, Shaun Nelms was on an upward trajectory as deputy superintendent at a large suburban school district. I was at the other end of the spectrum — at 63, a retired superintendent loving the life of a college professor.

While one of us was experiencing the daily challenges of an exciting career in educational leadership, the other was imparting the experiences of his exciting career to eager, much younger leadership candidates. Each of us thought we had a plan. Plans

change.

In March 2014, the Rochester, N.Y., school board president asked to meet with representatives of the University of Rochester’s Warner School of Education to discuss the future of East High School, the city’s largest and most

troubled school. Once the crown jewel of the city, East had become one of the lowest-performing high schools in the state with a graduation rate of only 33 percent.

Though the school officially had only 1,600 students, there had been more

than 2,500 suspensions during the previous year. Only 48.8 percent of 9th graders were promoted to grade 10, and we were told, not a single entering student had picked East as his or her first choice in the citywide lottery.

The state was

on the verge of closing East unless the district could create a partnership with a local university. The purpose of the board president’s visit was to ask the university to be the educational partnership organization, or EPO, to do that work.

As a retired superintendent, I was asked to lead the effort.

After some deep soul searching, we accepted the invitation, intending to focus our work on three major thrusts: social-emotional learning, teaching and curriculum, and collaboration.

This Content is Exclusive to Members

AASA Member? Login to Access the Full Resource

Not a Member? Join Now | Learn More About Membership

An ‘All In’ Commitment to Restorative Practices

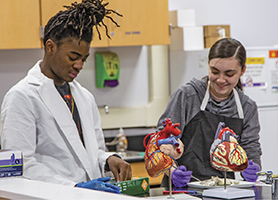

When we started working at Rochester, N.Y.’s East High School in 2015, Shaun Nelms and I thought we were ready for anything.

Both of us grew up in tough city neighborhoods, and each of us had led schools with complex issues. Yet when we walked the halls of East for the first time, we quickly realized students were trying to survive in a system not designed for their success.

The school environment was tense.

More than 2,500 suspensions had been handed out at East the year before and, according to staff, many more never were officially recorded. Fights, weapons, drugs and gangs were all prevalent. Since the University

of Rochester partnered with East High School, student suspensions have dropped 90 percent. Serious incidents took a precipitous dive. What changed?

Two elements of the turnaround plan focused on scholar dignity. The punitive system of student

discipline was replaced by a building-wide commitment to restorative practices. Student agency was embedded in the school’s mission statement.

As a behavioral management process, implementing restorative practices is not easy, and it

required an “all in” commitment of all faculty and staff. Students and staff members learned to resolve conflict in “circles,” taking turns speaking and listening.

Every staff member received some training, especially

those who supervised school hallways and other public areas. East added a social worker at each grade level who managed the restorative practices process.

To support that mindset, East features a daily “family group” time. Every

faculty member and every school leader, including the superintendent, participates in family group. Scholars are organized into groups of 10-12, each facilitated by a teacher, staff member or administrator. This is where student voice and thus student

agency is nurtured. It’s also where we hear of student concerns and can get out in front of tension and conflict.

Students still sometimes get suspended, and the hallways do not resemble Sesame Street. But in our annual student surveys,

scholars report they feel safe at school, something we don’t think we would have heard six years ago.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement