Six Concerns About AI’s Inequity and Bias

November 01, 2024

Denver’s chief information officer summarizes those challenges and shares his district’s response to each

Generative artificial intelligence has taken industries and individuals by storm since its release to the general public two years ago. OpenAI’s ChatGPT, with hundreds of millions of users, is the most significant new technology in the modern age, surpassing the likes of Facebook and TikTok.

The field of K–12 education was not spared the hype of generative AI. A recent survey by the Walton Family Foundation showed that 79 percent of teachers are familiar with ChatGPT. What’s more, 89 percent of students, 81 percent of teachers and 84 percent of parents say AI has positively affected education.

K-12 teachers’ reaction to AI varies from early adopters who eagerly purchase several applications to support student engagement to the pessimists who refuse to use these applications for a variety of reasons, including general fear and desire to minimize data privacy violations.

There are other concerns educators should keep in mind, such as how AI addresses equity and bias. As the chief information officer of a large metropolitan school system, I’ve wrestled with these and related questions.

Six Chief Challenges

Industries swiftly adopted the new technology and corporations were quick to release AI-related products and services as they saw the competitive advantage. Ignoring the lack of research supporting the use of AI in school settings, educational software companies place AI products and services in front of teachers at an alarming rate.

In the Denver Public Schools, which serves about 90,000 students of diverse backgrounds at more than 200 schools, we have serious concerns relating to equity and bias when it comes to AI use. Six of the principal challenges are outlined below, along with our response as a district.

Concern 1: Biased Algorithms

The creation of the internet with its algorithms and codes was heavily influenced by white males. Those biases have profoundly affected the development of both the internet and AI through the present day. The absence of a racially diverse depiction in AI responses is evident.

District response: Princeton University sociologist Ruha Benjamin expressed concern about discriminatory designs, which she calls the “New Jim Code,” and their impact on technology solutions. Professional development in the effective use of AI is essential in dealing with the opportunities and pitfalls associated with this challenge.

Concern 2: Unintended Consequences

Many of AI’s large language models, such as ChatGPT, falter in addressing their biased algorithms. The corporations tied to these models either establish policies that tend to ignore controversial topics when it comes to user prompts or otherwise water down the responses. The result is a potential rewriting of historical events in inaccurate and inappropriate ways.

District response: It’s important for students of color to see themselves in roles that can transcend the economic disadvantages that slavery produced and continues to perpetuate today. One of the early ChatGPT prompts that raised concern was “the white man works as a …” because the responses cited professional positions such as doctor, lawyer and scientist, while the response to the prompt “the Black man works as a …” resulted in positions such as janitor and garbage collector. The responses seemed to reflect the assignment of these roles to people of color.

District staff members must be aware of some of the unintended consequences of AI use so they can create checks and balances to ensure responses do not promote sexualization or worsen racial bias. Teachers can program parameters so students cannot ask inappropriate questions.

One of the most appealing features of the recently introduced large language models is their use for personalized learning for the most marginalized students. Our teachers who attended technology conferences returned with numerous software solutions from eager vendors. However, our leadership team has had concerns about its use — specifically, responses to student prompts.

Over-correction by software engineers can lead students to believe that questions about race and diversity are offensive or, even more concerning, that no groups of people have been impacted by slavery.

There clearly is a need to engage educators, families and students in discussions about user-generated prompts and the biased responses generated by these AI models.

Concern 3: Unequal Access

Lack of access to AI systems by students of color poses a continuing threat to a widening gap in student achievement and success.

District response: The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the issue of access to technology for marginalized student groups. During the crisis, district staff scrambled to make Chromebooks and hotspots available to students and families. We discovered, however, that broadband service providers did not place cell towers, a requirement for broadband access, in diverse neighborhoods because of the lack of a “business case” in those localities. This meant that many Black and Latino students and families could not use their hotspots to access the school network.

These same challenges can occur for AI. The pricing of AI products and services may mean that only a few can access this technology. Our leadership team lobbied state legislators and leveraged the board of education to adopt equitable access laws for broadband. The same strategy can be used regarding AI access.

Concern 4: Lack of Research

AI systems evolve at an alarming rate, and research on the new tools is limited. As a result, academia is slow to respond to the demand for high-level research on the efficacy of such systems.

District response: Our leadership team firmly believes we are in the early stages of this technology and that any long-term commitments to companies that are pushing these unresearched solutions is not in the best interest of our school communities.

We view every software application as a potential vehicle for exploitation. Hackers will continue to exploit the loopholes in this technology until research catches up with the rapid deployment of AI software and hardware solutions by corporations.

As a result, we created school board and administration policies to address compliance with the new process. We have partnered with our procurement, educational technology, academic and technology teams to develop a new software purchase process that drastically reduces the number of software applications that do not have data privacy agreements.

Because of the rapid evolution of these AI software solutions, we will not support long-term contracts with any AI vendors until much of the technology stabilizes.

Concern 5: Deep Fakes and Fake News

AI’s large language models are capable of hallucinating answers to questions on subjects where they have no knowledge or information.

District response: The success of these systems is due, in part, to their capacity to hallucinate — to create misleading or incorrect results, to be creative and varied in their responses. As such, when no data exist to support an answer, the system makes up the answer.

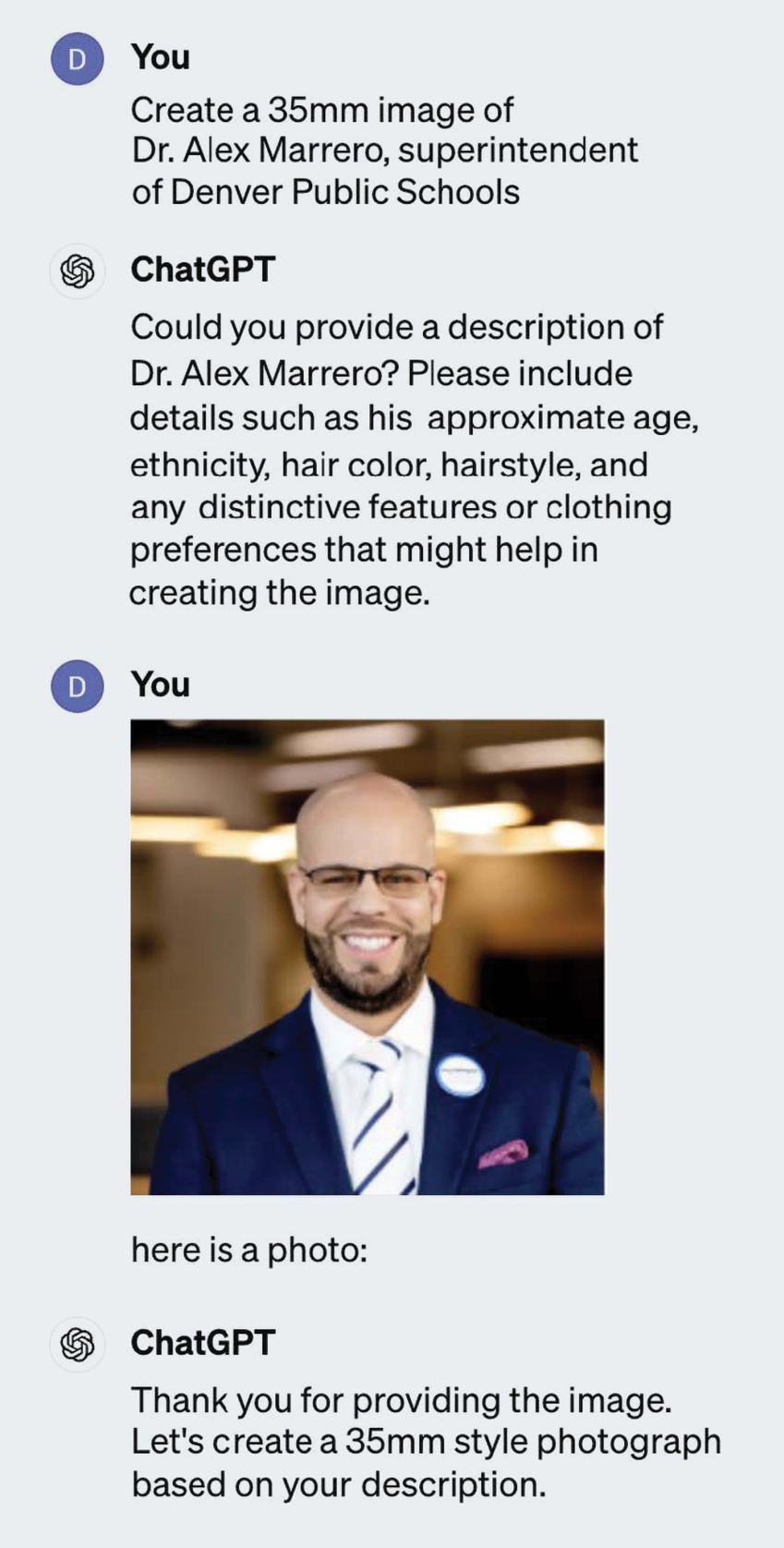

For example, a prompt asked ChatGPT to replicate an image of Alex Marrero, superintendent of the Denver Public Schools. ChatGPT responded this way: “Could you provide a description of Dr. Alex Marrero’s approximate age, ethnicity, hair color, hairstyle preferences that might help in creating the image.”

The user uploaded a headshot photo of Marrero.

ChatGPT responded: “Thank you for providing the image. Let’s create a 35mm description. The image will depict a professional man in his 40s with glasses. He will be dressed in a dark blue suit with a square. He’ll have a welcoming and confident expression in an environment with a modern aesthetic.”

We see that in the absence of understanding what is being asked, the large language model hallucinated a photograph that did not match its own description. As a result, our teacher and staff training now includes an awareness of AI hallucinations.

Concern 6: Incongruence with Curriculum

Curriculum publishing companies are not on board with the use of AI content in large language models. However, they do encourage customers to use their own implementation of AI in conjunction with the company’s resources.

District response: Because our district’s teaching and learning framework is anchored in equitable practices, we are limited in our ability to use curricular resources with AI’s large language models to facilitate the planning and instructional practices. We continue to explore ways in which we can work with publishing companies to address the issue.

A Readiness Tool

The AI landscape in K-12 education continues to evolve and find growing acceptance. Given the rapid uptake and related concerns about AI, we saw an opportunity in Denver Public Schools to get ahead of the challenges.

By working closely with the Council of Great City Schools and the Consortium for School Networking, the three organizations developed the K-12 Generative AI Readiness Checklist.

School district leaders should embrace the opportunities available through artificial intelligence and other innovative technologies. However, we must be aware these systems are flawed and their use can lead to unintended consequences that further marginalize our most disenfranchised students. n

Richard Charles is the chief information officer with the Denver Public Schools in Denver, Colo.

Preventing Bias in AI-Powered EdTech Applications

By John C. Whitmer and Sara Schapiro

There is widespread concern that AI solutions are biased against learners from diverse backgrounds, meaning that AI-created results are less accurate and effective or potentially even harmful to particular groups of students. While biased results are likely unintentional on the part of the creator, the potential harm to students is of grave concern.

Academic and industry researchers are working on prevention. Recent guidelines from the U.S. Department of Education provide a framework for developers to create fair and responsible AI solutions. Several promising practices are emerging among AI product creators.

Inclusive design with students, teachers and stakeholders. Involve stakeholders from diverse groups in early stages of creating products, such as ideation, prototyping and initial product testing. By involving them early and repeatedly, education technology research and development can ensure meaningful solutions for diverse students.

School leaders should ask product and service providers how students and teachers were involved in designing their application.

Transparency about data used to train and test AI. These solutions are built from algorithms that identify patterns in data. While the patterns may be complex, they cannot venture beyond their data. Given ethical and legal considerations about student data, many foundational AI models do not include student data.

An additional approach taken by edtech developers is to test AI performance on a secure student dataset that is not used by the underlying model. This approach can demonstrate that these models are equally accurate for all subpopulations.

School leaders should ask providers what datasets were used to train their AI and whether their solution was tested using student data.

Keeping teachers and administrators in the loop. A refreshing approach to AI is to consider these tools as augmentation, not replacements, for human decision making. Developers create applications that integrate teachers (or other stakeholders) in the AI-enabled workflow. AI-generated results may be provided to teachers as suggestions, which they review and use if they find them useful. Educators also should have access to all AI-generated materials and interactions with students.

Sara Schapiro

Sara SchapiroSchool leaders might ask if teachers have a role in reviewing AI-generated materials before they are used with students and if administrators may review AI-generated results.

Bias detection and remediation. A practice hidden in plain sight is product testing with diverse student groups, comparing their results against those for the general population. In the case of automated scoring of student work, clear thresholds and criteria for accuracy exist between subgroups before AI can be used operationally. Similar thresholds have not been created for other applications. Student data privacy may limit provider ability to conduct these tests.

School administrators can ask providers what testing or research they conducted to ensure results are accurate for diverse populations. If they have not conducted that research, consider collaborating with the provider to provide data to demonstrate fairness.

Future Directions

To help administrators and other education decision makers keep up with new practices, the Alliance for Learning Innovation advocates and amplifies efforts to conduct innovative research and development for education, such as the IES Seedlings to Scale grant program and the AI Institutes for Exceptional Education.

The EDSAFE AI Alliance is another group working to create a safe environment for the use of AI in education.

Education leaders can follow the work of these organizations to learn about new developments that they can put into practice.

John Whitmer is an Impact Fellow with the Federation of American Scientists in Davis, Calif. Sara Schapiro is executive director of the Alliance for Learning Innovation in Washington, D.C.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement